I recently wrote about our experience migrating to cloud computing to support development and QA activities. Our cloud enables us to support more platforms, at lower cost, and with less complexity than the fleet of physical servers it replaced. But I didn’t have room to talk about one important decision in our migration: whether to build a private cloud or use an existing public cloud like Amazon EC2 or Rackspace Cloud.

For us, the decision was easy. The public cloud is unsuitable for three reasons: platforms, bandwidth and money. First, the public cloud doesn’t support the platforms we need for testing. Second, uploading data to the public cloud takes way too long by today’s agile, continuous development standards. Finally, and probably most interesting to you, the public cloud is surprisingly expensive. In fact, I estimate that the public cloud would cost us more than twice as much as our private cloud, every year.

Public clouds don’t support all of our platforms

My product is supported on a smörgåsbord of x86-based platforms — various incarnations of Windows, from XP to Vista to Windows 7; and a variety of Linux distributions from RHEL4 to Ubuntu 10. Our quality standards demand that we run the platform-dependent portion of our test suite on every supported platform. Pretty standard stuff, I imagine. Too bad for us then that you can’t run XP, Vista or 7 in the cloud (see also here and here).

Bandwidth to the public cloud stinks

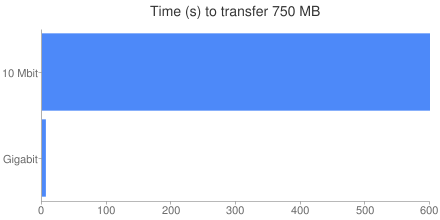

My company is connected to the Internet via a puny 10 Mbit EoC pipe. In comparison, our internal network uses fat GigE connections. Under ideal conditions, it takes 100x longer to transfer data to the public cloud than to our private cloud. Think about that for a second. Heck, think about it for 600 seconds: that’s how long it would take me to upload 750 MB, the total size of our install packages. And that’s best case. When’s the last time you hit the advertised upload speed on your Internet connection?

Transferring those files on our intranet requires a barely measurable 6 seconds:

Adding that kind of delay to our CI builds is just not acceptable.

The public cloud is expensive

Many people assume that the public cloud will be cheaper than a private cloud. A day’s worth of compute time on Amazon EC2 costs less than a Starbucks latte, and you have no upfront cost, unlike a private cloud which has substantial upfront capital expenses. But it pays to run the numbers. In our case, the public cloud is more than twice the cost of a private cloud:

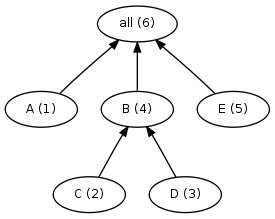

I split the costs into two buckets, because we have two fundamentally different usage models for the VM’s in our cloud. First are the systems used by our continuous integration server to run automated tests. Each CI build uses 12 Linux and 8 Windows systems, one for each supported platform. Our testing standards require that those systems are dual-core, but the work load is light since they just run unit tests and simple system tests. We have three such blocks of 20 systems, so we can run three CI builds simultaneously. Because the CI server never sleeps, these systems are always on.

Second are the systems used day-to-day by developers for testing and debugging. Each developer may use just a few systems, or more than a dozen depending on their needs. It’s hard to pin down the precise duty cycle, but eyeballing data from our cloud servers I estimate we have about 80 systems in use per day, for about 8 hours each. They are split roughly 50/50 between Linux and Windows. Two-thirds of the systems are single-core, and the rest are at least dual-core.

Pricing the public cloud

Once you know the type and quantity of VM’s you need, and for how long, it’s straightforward to compute the cost of the public cloud. Because I’m most familiar with Amazon EC2, I’ll use their pricing model. For our CI systems, we would use a mix of Medium and Large instances to match our requirements for multi-core and 64-bit support. Because they are always-on, we’d opt to use the Reserved instance pricing, which offers a lower hourly cost in exchange for a fixed up-front reservation fee.

For developer systems, we would use On-Demand instances, with a mix of Small and Large instances:

| Continuous integration systems | |||

| Medium instances | |||

| Annual fee | = | $15,015.00 | (33 systems at $455 per system) |

| Linux usage fee | = | $14,716.80 | (21 systems, 24 hours, 365 days, $0.08 per hour per system) |

| Windows usage fee | = | $15,242.40 | (12 systems, 24 hours, 365 days, $0.145 per hour per system) |

| Large instances | |||

| Annual fee | = | $24,570.00 | (27 systems at $910 per system) |

| Linux usage fee | = | $21,024.00 | (15 systems, 24 hours, 365 days, $0.16 per hour per system) |

| Windows usage fee | = | $25,228.80 | (12 systems, 24 hours, 365 days, $0.24 per hour per system) |

| Subtotal | = | $115,797.00 | |

| Development systems | |||

| Small instances | |||

| Linux | = | $4,940.00 | (26 systems, 8 hours, 250 days, $0.095 per hour per system) |

| Windows | = | $6,760.00 | (26 systems, 8 hours, 250 days, $0.13 per hour per system) |

| Large instances | |||

| Linux | = | $10,640.00 | (14 systems, 8 hours, 250 days, $0.38 per hour per system) |

| Windows | = | $15,600.00 | (14 systems, 8 hours, 250 days, $0.52 per hour per system) |

| Subtotal | = | $37,940.00 | |

| Total | = | $153,737.00 | |

Pricing the private cloud

It’s somewhat harder to compute the cost of a private cloud, because there is a greater variety of line-item costs, and they cannot all be easily calculated. The most obvious cost is that of the hardware itself. We use dual quad-core servers which cost about $3,000 each. Six of these servers host our CI VM’s. Note that this is only 48 physical cores, but our CI VM’s use a total of 120 virtual cores. This is called oversubscription, and it works because the load on the virtual cores is light — if each virtual core is active only 30-50% of the time, then one physical core can support 2-3 virtual cores.

We use 15 servers for our on-demand development VM’s. Unlike the CI systems, these VM’s are subject to heavy load, so we cannot oversubscribe the hardware to the same degree.

The next obvious cost is the electricity to power our servers, and of course the A/C costs to keep everything cool. Our electrical rate is about $0.17 per KWh, and we estimate the cooling cost at about 50% of the electrical cost.

Finally, we must consider the cost to maintain our 21 VM servers. To compute that amount, we must first determine how much of a sysadmin’s time will be spent managing these servers. Data from multiple sources shows that a sysadmin can maintain at least 100 servers, particularly if they are homogeneous as these are. Our servers therefore consume at most 21% of a sysadmin’s time.

Next, we have to determine the cost of the sysadmin’s time. I’m not privy to the actual numbers, but salary.com tells me that a top sysadmin in our area has a salary of about $90,000. The fully loaded cost of an employee is usually estimated at 2x the salary, for a total cost of $180,000 per year.

Here’s how it all adds up:

| Continuous integration systems | |||

| Hardware | = | $6,000.00 | (6 dual, quad-core systems at $3000 each, amortized over 3 years) |

| Personnel | = | $10,800.00 | (6% of a fully-loaded sysadmin at $180,000) |

| Electricity | = | $3,082.65 | (6 systems x 345w x 24 hours x 365 days x $0.17 per KWh) |

| Cooling | = | $1541.33 | (50% of electricity cost) |

| Subtotal | = | $21,423.98 | |

| Development systems | |||

| Hardware | = | $15,000.00 | (15 dual, quad-core systems at $3000 each, amortized over 3 years) |

| Personnel | = | $27,000.00 | (15% of a fully-loaded sysadmin at $180,000) |

| Electricity | = | $7,706.61 | (15 systems x 345w x 24 hours x 365 days x $0.17 per KWh) |

| Cooling | = | $3,853.31 | (50% of electricity cost) |

| Subtotal | = | $53,559.92 | |

| Total | = | $74,983.90 | |

Why is the public cloud so expensive?

I wasn’t surprised that the public cloud was more expensive, but I was surprised that it was that much more expensive. I had to figure out why it was so, and I think it comes down to two factors. First, we need 64-bit dual-core VM’s for our tests, but 64-bit support is only available on Large or better instances, which are at least 2x the cost of Medium instances. We would be forced to pay for more (virtual) hardware than we need.

Second, we benefit significantly by oversubscribing the hardware in our private cloud with 2.5 virtual cores per physical core. I have no doubt that Amazon is doing the same thing behind the scenes, but — and this is the real kicker — virtual cores in the public cloud are priced assuming a one-to-one virtual-to-physical ratio. Put another way, even though the public cloud provider is certainly oversubscribing their hardware and you’re only getting a fraction of a physical core for each virtual core, you still have to pay full price for those virtual cores. For all that increased hardware utilization is touted as a benefit of cloud computing, it only applies if you own the hardware.

Does it ever make sense to use the public cloud?

The results here are pretty dismal, but I think there are situations where the public cloud is the best choice. First, although private is cheaper in the long term, it requires a substantial upfront investment just to get off the ground — $63,000 for the hardware in our case. You may not have that kind of capital to work with.

Second, if your needs truly are “bursty”, the public cloud on-demand pricing is actually pretty competitive. Of course, you have to be really good about managing those VM’s — if you leave them powered on but idle, you still pay usage fees, which will quickly inflate your expenses.

Finally, if you’re just “testing the waters” to see if cloud computing will work for you, it’s definitely cheaper and easier to do that with a public cloud.

Private clouds for dev/test

Our private cloud has been a powerful enabling technology for my team. If you’re in a similar situation, you should seriously consider private versus public. You might be surprised to see how favorably the private cloud compares.