The fundamental unit of work in ElectricAccelerator is the job. Most of the time, you can think of a job as all the commands that must be run in order to create or update a single build output, but in truth that describes only one type of job. There are actually several different job types, each with a distinct purpose in the structure of a build and the way Accelerator executes the build. You can determine the type of a job from the type attribute on the <job> tag in Accelerator annotation files.

Having some familiarity with the job types and their use will make it easier for you to understand Accelerator performance and behavior, so I wrote this guide to introduce them. First I’ll describe the jobs used by ElectricMake (emake), and then the jobs used by Electrify.

ElectricMake jobs

In order to make the descriptions more concrete, I created a simple reference build that uses each of the most common job types, so you can see exactly how the jobs relate to a real build. Here’s the reference build makefile:

prog:

@$(MAKE) sub/prog

@cp sub/prog ./prog

sub/prog: sub/main.c

@cat $< > $@

setup:

rm -rf prog sub

mkdir sub

echo "int main() { return 0; }" > sub/main.c

touch prog2

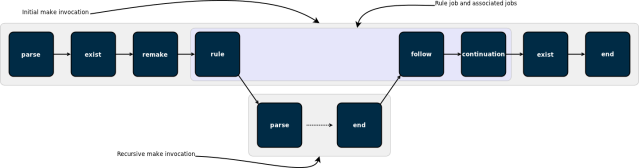

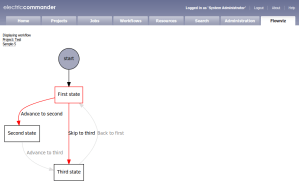

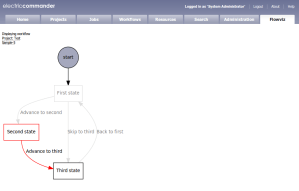

To run the build, first run emake setup, which will create the files and directory structure needed by the build, then run emake –emake-maxagents=1 –emake-annodetail=basic –emake-annofile=emake.xml prog prog2. That will produce a build with thirteen different jobs, in two different make instances. Here’s an overview of how those jobs fit together (click for a larger image):

parse

The first job in any make invocation (and therefore the first job of any emake build) is a parse job, during which emake reads and interprets the makefiles used in that make instance. The output of a parse job is a list of all the jobs in the make instance, along with a list of targets that must be built, the commands to build those targets, and the relationships between them.

exist

Existence jobs (marked as type “exist” in annotation) are used to check for the existence of makefiles and command-line goals for which no rule was found. In our reference build, you can see an existence job in the top-level make for the makefile itself, as well as one for the file prog2, which has no rule in the makefile.

remake

Remake jobs are at the center of emake’s emulation of GNU make makefile remaking feature. In a remake job, emake checks every makefile that was read during the parse job for two things:

- Is there a rule to rebuild the makefile; and

- Was the makefile actually rebuilt (because it was out-of-date).

If any makefile was rebuilt, then emake restarts the make instance — all the way back to the parse job.

Because makefile remaking is a gmake-specific feature, you will only see remake jobs when emake is emulating gmake — not when it’s emulating NMAKE.

One last note about remake jobs: emake overloads the use of the <failed> tag inside a remake job to indicate not failure, but whether or not the job determined that the make instance should be restarted. If yes, then the remake job will include a <failed> tag with the code attribute set to 1; if not, then the remake job will have no <failed> tag.

rule

Rule jobs are the real workhorses of a build. Each rule job encapsulates the commands needed to update one target in the build — literally the body of a rule from a makefile — and a rule always has an associated output target (or targets), which is identified by the name attribute of the job tag in annotation. In our reference build, the rule job in the toplevel make instance corresponds to this rule in the makefile:

prog:

@$(MAKE) sub/prog

@cp sub/prog ./prog

If you look at the annotation for the job you’ll notice that only $(MAKE) sub/prog is actually in the rule job — because the cp sub/prog ./prog was automatically split into a continuation job when emake detected the recursive make invocation.

follow

A follow job serves two purposes. First, it is a connection point that allows emake to tie the end job of a recursive make invocation back into the ordered list of jobs in the parent make. Second, it is the means by which emake propagates the error status of a recursive make to the parent make.

Follow jobs always have an associated rule or continuation job, identified by the partof attribute on the job tag in annotation. That is the job that spawned the recursive make which the follow job is associated with. Of course, not all rule and continuation jobs have an associated follow job — follow jobs only show up when a recursive make was invoked.

continuation

A continuation job represents the “leftover” commands that follow a recursive make invocation in a rule (or continuation) job. In our reference build, emake creates a continuation job for cp sub/prog ./prog, because that command follows a recursive make invocation. Continuation jobs, like follow jobs, are always associated with a rule (or another continuation) job, identified by the partof attribute on the job tag in the annotation.

The reason for splitting the extra commands into a separate job is simple: that allows emake to easily specify the serial order of those commands relative to the jobs in the recursive make — the commands in the continuation come after the jobs in the recursive make.

end

The last job in every make instance (and therefore the last job of every emake build) is an end job. End jobs exist primarily to handle end-of-the-make cleanup, such as removing intermediate targets or temporary inline files that were created while executing the other jobs in the make.

(Not pictured) subbuild

Subbuild jobs, which were not used in the reference build, are part of emake’s subbuild feature. They are simply a mechanism to inject a recursive make invocation into the build, just as you would get if you had a rule job with a $(MAKE) command, but without the tedium of actually running that command.

Electrify jobs

Electrify uses much of the same underlying machinery that emake does, but it has its own set of job types for its particular needs.

alpha

Every electrify build starts with an alpha job, which is a trivial placeholder marking the start of the list of jobs.

external

External jobs represent commands invoked by the electrified build tool which are distributed to the cluster. These are similar to emake’s rule jobs, except they will only ever run a single command, while rule jobs may run any number of commands.

update

Update jobs represent filesystem modifications made by commands invoked by the electrified build tool but not distributed to the cluster. These modifications are detected with the aid of electrifymon.

omega

Every electrify build ends with an omega job, which, like the alpha job, is a trivial placeholder.

Conclusion

I hope you’ve found this post informative. Questions or feedback? Please feel free to comment below!