Recently we invited a Scrum coach to Electric Cloud to teach us how to get started with the Scrum model of agile development. On the first day we played a game intended to introduce us to the core elements of Scrum: plan, do, inspect, adapt (or “plan, do, check, act”; or “the Deming cycle”). Without getting into a deeper discussion of Scrum itself, I thought I would share my team’s performance in this fun little game. If you’re familiar with ElectricAccelerator, our game strategy will come as no surprise: it exploits parallel processing and horizontal scalability to improve performance.

The game was simple: we were given a bucket of rubber bouncy balls and instructed to pass balls from person to person, until every member of the team had touched the ball. For each ball that completed the circuit we earned one point; for each drop we were penalized three points. A few rules made the game more interesting. First, it was forbidden for two people to touch a ball at the same time — there had to be “air time” between individuals. Second, we could not pass balls to the person directly to our left or to our right. Finally, there was a time limit (just like a sprint): we had only 2 minutes to pass balls in each round.

At the start of the game, we were given 5 minutes to plan our strategy and make a prediction of how many balls we would pass. Between each round we had 3 minutes more to modify our strategy based on our experience in the previous round and make a new prediction for the next round. If you are familiar with Scrum you’ll recognize the analogy to story points.

In total we had 12 players plus one scribe (me) that was tasked with counting the number of balls passed and dropped.

Round 1 (plan: 0; actual: 29)

Our first planning phase was best described as chaotic. It wasn’t actually clear who was on our team or not, due to some stragglers to the activity. We weren’t sure about the constraints. Everybody had ideas about how best to pass the balls, so everybody was talking at once. It seemed simple, but in fact we had barely gotten everybody in place when the 5 minute prep time elapsed. We did manage to agree on the three key elements of our strategy though:

- Dropping balls into the cupped hands of the receiver, rather than throwing them, to minimize the risk of dropping balls.

- Two rings of players, one inner and one outer, facing each other. Balls would be passed in a zig-zag between the rings.

- Parallel passing. Everybody would be either passing or receiving at all times.

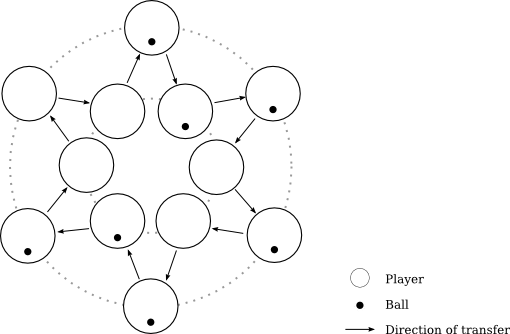

This diagram shows the positions of the players, as well as which players had a ball at the start of the round:

As you can see, we had too many balls “in play” when we started, given our strategy — a direct consequence of unclear communication during the planning phase. The surplus balls were dropped almost immediately. Our final score for this round was 29: 1 point for each of 35 balls passed, minus 6 points for 2 balls dropped.

Round 2 (plan: 50; actual: 72)

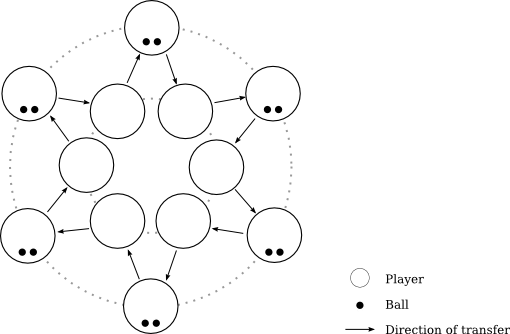

Round 1 demonstrated that our core strategy was sound, but to improve performance we decided to make a couple tweaks. First, we made certain that we were in agreement about which players would start with balls: only those in the outside ring. Second, we realized we could improve throughput by passing two balls at a time, instead of just one. With our drop-into-cupped-hands strategy this was hardly more risky than one ball at a time. We predicted that we would pass 50 balls, about 60% more than we did in round 1. Here’s the updated diagram showing the starting positions of the players and balls for round 2:

Our score in round 2 was 72: 72 balls passed, with zero dropped.

Round 3 (plan: 120; actual: 60)

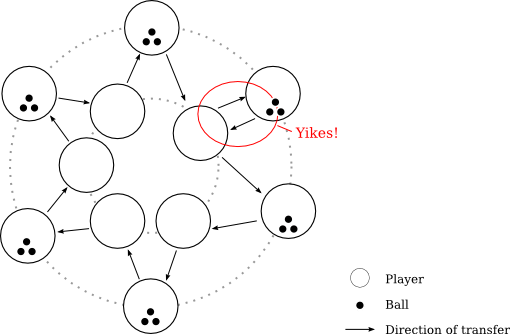

At this point we believed we had everything worked out. We increased the balls-per-pass to three and predicted that this would result in about 120 balls passed. But during the planning phase one of our players abruptly left — to be honest I’m not even sure who it was or why they stepped away. All I know is that suddenly we had only 11 players instead of 12, which left us with 6 on the outer ring but only 5 on the inner ring. We didn’t realize the problem until people started lining up in position near the end of the planning period. With the clock ticking we made an exceptionally poor decision about how to handle the mismatch: one of the inner ring players would serve as receiver for two of the outer ring players. First they would receive from player A, then pass to player B; then immediately receive the balls back from player B before sending them on to player C. Sounds complicated, right? It was. Here’s the updated diagram:

This proved was disastrous for our performance. At speed, it was (understandably) hard for the player serving double-duty to efficiently execute the elaborate sequence of exchanges. In addition, we were careless when we grabbed the extra balls we needed: although most were consistently round, a few were those oddly shaped rubber rocks which move in unpredictable ways. These misshapen lumps of rubber are just a bit harder to catch than regular balls, and that slowed us down. Our final score in this round was just 57: 60 balls passed, one dropped.

Round 4 (plan: 120; actual: 123)

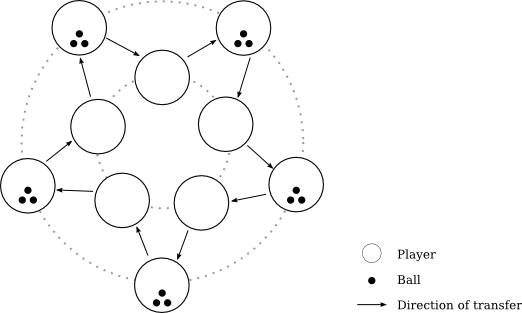

The obvious problem in round three was the mismatch in the sizes of the inner and outer rings. The solution was obvious too: remove one player from the outer ring to restore equilibrium. There was just one problem. According to the rules of the game, a ball had to be touched by every player in order to count as having been passed. What could we do? We pled our case to the coach, who agreed to let us have one person sit out this round — a demonstration of another fact of agile development: sometimes a team can be made more productive by having fewer people on it. With 5 players on each ring, we again predicted that we would pass 120 balls. Here’s how the layout looked for this round:

This was our best round yet with a final score of 123: 135 balls passed, with only four drops.

Review

Overall I was really pleased with our performance in this game — granted, the point of the exercise was not actually to see how many balls we could pass around, but to experience the plan-do-inspect-adapt cycle directly. And we certainly did that too. But come on! How can you not be excited by a more than 4x improvement in throughput from round 1 to round 4? I’m not surprised though. After all, speed is the name of the game for ElectricAccelerator. This is what we do. That we got there by applying the same strategies to this game that we use in Accelerator itself — icing on the cake.

Later that night I realized an error in our execution on round 4 though. We chose to even out the rings by dropping one player from the outer ring, when we could just as easily have added a player to the inner ring: me. As scribe, I did not actively participate in the ball passing, only the planning and review. But there was no particular reason I couldn’t have stepped in. That would have increased our throughput by 20% (by increasing the number of balls in play from 15 to 18). I think we could have exceeded 150 balls passed with that configuration. So in the end, the game was a great demonstration of what is probably the most important concept from Scrum: there’s always room for improvement.